Before I kick off this week’s blog post, I want to let everyone know some good news. Optical Sloth gave a review of Sunnyville Stories episode 2 so go on over and check out the site. While you’re there, check out some of the other comics reviewed. A couple of them are quite impressive.

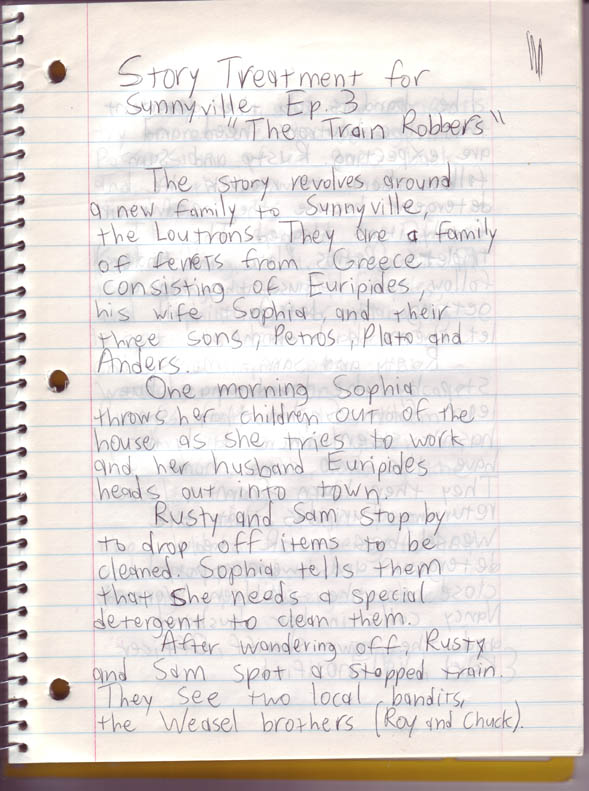

Last week, I started to explain the basics of writing comics. I discussed the reversal of fortune and the recognition of that reversal. I’ll talk some more about the writing process. Some of you out there may wonder how exactly do I write a story. Well, I’ll let you in on that very trade secret. My process is that I first get an idea. (Check my entry on generating ideas.) When I search for my ideas, I look in various places. Sometimes I draw upon my own personal experiences. For example, the fourth episode of Sunnyville currently in production, entitled “Don’t Answer Me”, was partly drawn on my own personal experiences of how I had to admit when I was wrong. Sometimes, I’ve drawn on the anime series that inspired Sunnyville, Maple Town. Elements of episode 1 were based on the very first episode of Maple Town in which Patty Rabbit and her family move to Maple Town, coming in on the train. Elements of episode 2 likewise were influenced by the second episode of Maple Town (titled in the USA “the Stolen Necklace”) where Patty Rabbit has a run-in with the local rich girl Fanny Fox. From there, I do a handwritten story treatment.

Again, this is not meant to be fancy. It’s just a basic rundown of the story, keeping in mind the basic elements of the reversal of fortune and recognition of that reversal. I don’t try to insert clever jokes or puns into this story treatment – the basic idea is just to get the premise of the story down. The treatment usually isn’t more than a few pages. Once I have the treatment written, I’ll use that, the intended theme of the story, and my notes on the characters to actually type up a script. There are a couple of different ways to work up a script for a comic. You might need nothing more than a page for a single page gag or four panel comic strip. A typical 30-40 page story like I do will need something more substantial.

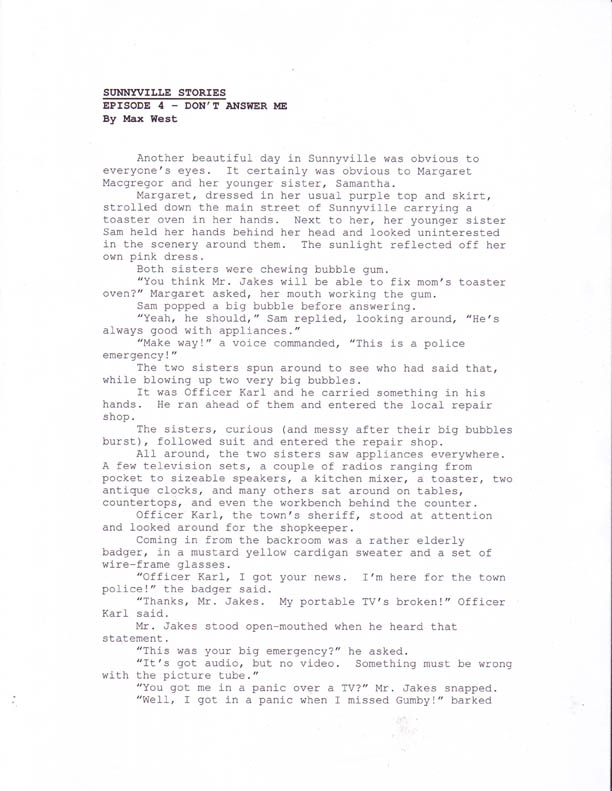

I usually type up a prose style script like the one you see here. Some people prefer this kind of script, but others may use a script sort of like that used for a movie or TV show. My advice is to try both methods out and see what works best for you.

I usually type up a prose style script like the one you see here. Some people prefer this kind of script, but others may use a script sort of like that used for a movie or TV show. My advice is to try both methods out and see what works best for you.

How detailed should you be in writing your comics script? Do you put in one or two sentences in to describe each panel or do you enter lengthy descriptions describing what the buildings look like, the smells in the air, the windows being dusty and what the sailor sitting by the pier is eating for lunch? It all depends. If you are both writer and artist, then you should probably find a balance that works out for you. If you are part of a team, then you should probably describe each page and panel as best as you can. Be VERY specific to your penciller or inker or colorist, etc. if you have a special vision in mind for your panel. If you want your characters to be wearing 1980s style clothing, describe it in detail. If you want your antagonist to be driving a 1959 Chevrolet Impala with cat’s eye lights and batwing tailfins, tell them in the script and maybe include a reference image or two. I should emphasize that no one method of writing scripts for comics is best; comics writing (much like other aspects of the art) is more of alchemy than science. Find what works for you and do it!

Now that we have my working process down and possible ideas for you readers how to compose your scripts, let’s take a closer look at the actual story. I described reversal of fortune and recognition of that reversal before, but a more solid structure for writing could be set up like this:

- The protagonist(s)

- The spark

- The escalation

- The climax

- The denouement

These five ingredients for your story structure – we’ll go over these in a moment. I want to cite though that these came out of the text Drawing Words and Writing Pictures by Jessica Abel and Matt Madden (I’ll clue you in on more good books for writing at the end of this post).

I’ll explain these elements a bit and use Sunnyville Stories episode 1 as an example. The protagonist is essentially the main character of the story. In this case, it’s our young newcomer to Sunnyville, Rusty Duncan. The spark is essentially what sets the story in motion. The spark disrupts the protagonist’s life and the protagonist must put things right again. In this case, the spark for Rusty is that he has come to a completely new town that is totally alien to him and he feels alone. So the challenge to Rusty is that he has to adapt to his new home and find something he likes about it. From there, we have the escalation. Rusty consistently has problems from a house that is in bad repair to exploring the unfamiliar surrounding territory to feeling alone without any friends. Basically, things have to get worse and/or challenges have to mount as the protagonists attempt to solve the problem. Do you think the story would have been any good if Rusty just waltzed into town, said a friendly hello to everyone, and the town’s children welcome him with open arms? That would have been nice for Rusty…but it would have been boring for the readers. That’s why escalation and conflict are very important to a story. Next, we come to the climax. The climax is where the story is resolved. It’s intended as a definitive ending and either the problem is resolved or it is not. The protagonist may not necessarily win or succeed, but they at least must have tried and/or had the ability to solve the problem. Episode 1 is essentially resolved when Rusty makes new friends at the welcoming party held for him and finds a new friend in Sam Macgregor. The denouement is usually at the end or may even be skipped altogether. It’s meant to tie up loose ends or maybe lead in to a sequel or future story.

That’s the basic idea of writing comics in a nutshell. Describing how to write comics or write in general would probably take up a whole blog in itself and would be better suited as a book. In fact, as I said I would, I’ll list some good texts for further reading.

Drawings Words and Writing Pictures by Jessica Abel and Matt Madden, First Second Publishing

The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics by Dennis O’Neil, Watson-Guptill

Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels by Scott McCloud, Harper Paperbacks

Poetics by Aristotle

The Elements of Style by William Strunk and E.B. White

I hope all of you found this post informative and helpful. If you have any comments or questions, feel free to post them here. Do you have your own ways of writing? If so, why not share them here with the rest of us? Subscribe via RSS or email if you haven’t already and check out the Sunnyville store for comics and prints to buy. Next week, I’ll actually get to the drawing part of comics! So until then, readers, bye-bye!

Pingback: How to Make Comics: Pencilling Comics | Sunnyville Stories